According to new research from Manchester Metropolitan University in the UK, aviation accounts for 3.5% of human activities that are driving climate change. Lead author of the study, David Lee, professor of atmospheric science at Manchester Metropolitan University and director of its Centre for Aviation, Transport and the Environment research group, said the findings show that two-thirds of the impact from aviation can be attributed to non-carbon dioxide emissions.

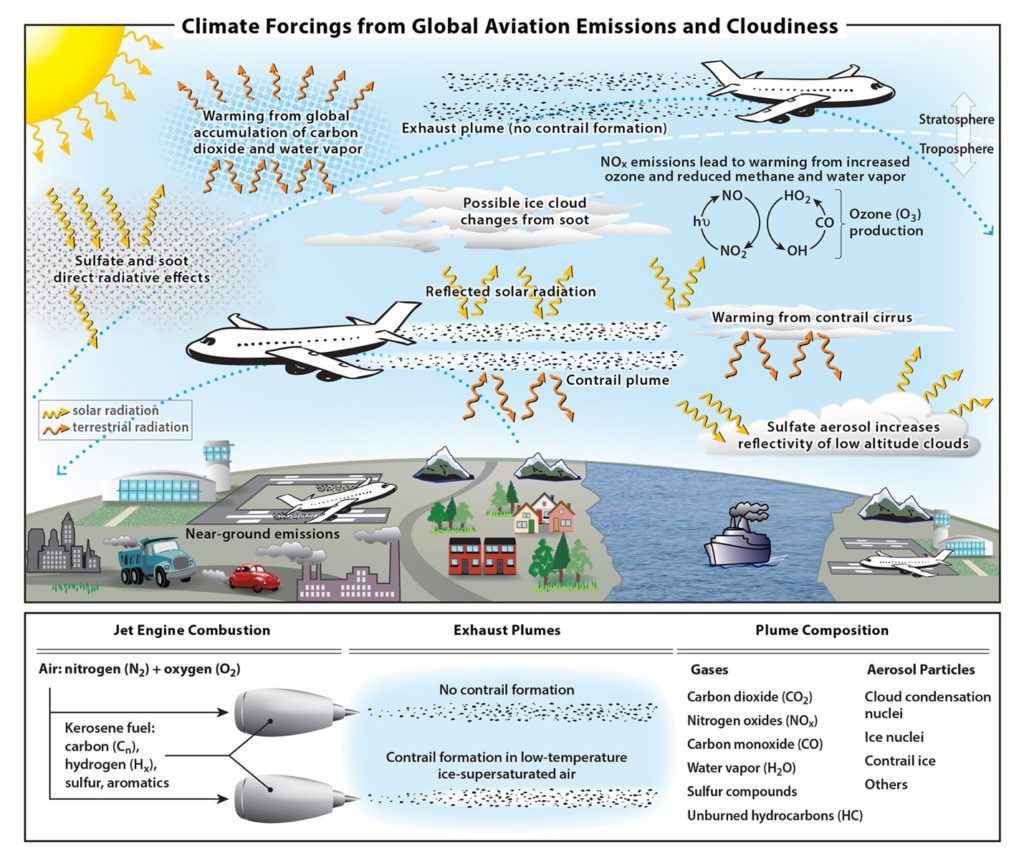

Researchers evaluated all of the aviation industry’s contributing factors to climate change, including carbon dioxide (CO2 ) and nitrogen oxide (NO2 ) emissions, in addition to the effect of contrails and contrail cirrus – clouds of ice crystals created by aircraft jet engines at high altitude. This was analyzed alongside the water vapor, soot and aerosol and sulfate aerosol gases – fine particles suspended in the air – found in the exhaust plumes emitted by aircraft engines.

The authors say the study is unique because it is the complete first set of calculations for aviation that uses a new metric introduced in 2013 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. This metric is called ‘effective radiative forcing’ (ERF) and represents the increase or decrease since pre-industrialized times in the balance between the energy coming from the sun and the energy emitted from the Earth, known as the Earth-atmosphere radiation budget.

Using the ERF metric, the team found that contrail cirrus’s impact is less than half that estimated previously but still the sector’s largest contribution to global warming, by reflecting and trapping escaping heat from the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide emissions represent the second largest contribution but unlike the effects of contrail cirrus, CO2’s effect on climate lasts for many centuries.

Lee explained, “Given the dependence of aviation on burning fossil fuel, its significant CO2 and non-CO2 effects, and the projected fleet growth, it is vital to understand the scale of aviation’s impact on present day climate change, especially in view of the requirements of the Paris Agreement to reach ‘net zero’ CO2 emissions by around 2050.

“But estimating aviation’s non-CO2 effects on atmospheric chemistry and clouds is a complex challenge for contemporary atmospheric modeling systems. It is difficult to calculate the contributions caused by a range of atmospheric physical processes, including how air moves, chemical transformations, microphysics, radiation, and transport.”

“But estimating aviation’s non-CO2 effects on atmospheric chemistry and clouds is a complex challenge for contemporary atmospheric modeling systems. It is difficult to calculate the contributions caused by a range of atmospheric physical processes, including how air moves, chemical transformations, microphysics, radiation, and transport.”

Lee and his team calculated that the cumulative CO2 emissions of global aviation throughout the course of the industry’s entire history – defined as between 1940 and 2018 – were 32.6 billion tons. Approximately half the total cumulative emissions of CO2 were generated in the last 20 years alone, attributed largely to the expansion of the number of flights, number of routes and fleet sizes, particularly in Asia, though partially offset by improvements in aircraft and jet engine technology, larger average aircraft sizes and increasing efficiency in the use of aircraft capacity to fit more passengers in the same space.

The research team estimated the figure of 32.6 billion tons accounted for 1.5% of total CO2 emissions ever at that point. When the non-CO2 impacts were factored in, aviation’s was calculated to be 3.5% of all human activities that drive climate change.