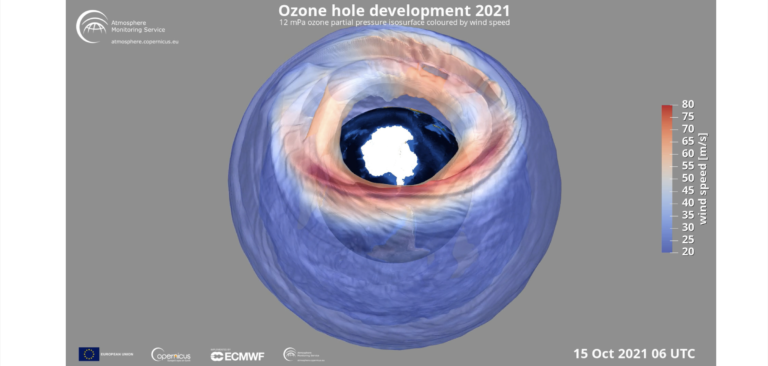

Scientists from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) have confirmed that the 2021 Antarctic ozone hole season has almost reached its end. The closure is expected to occur only a few days earlier than in 2020, which was the longest-lasting since 1979.

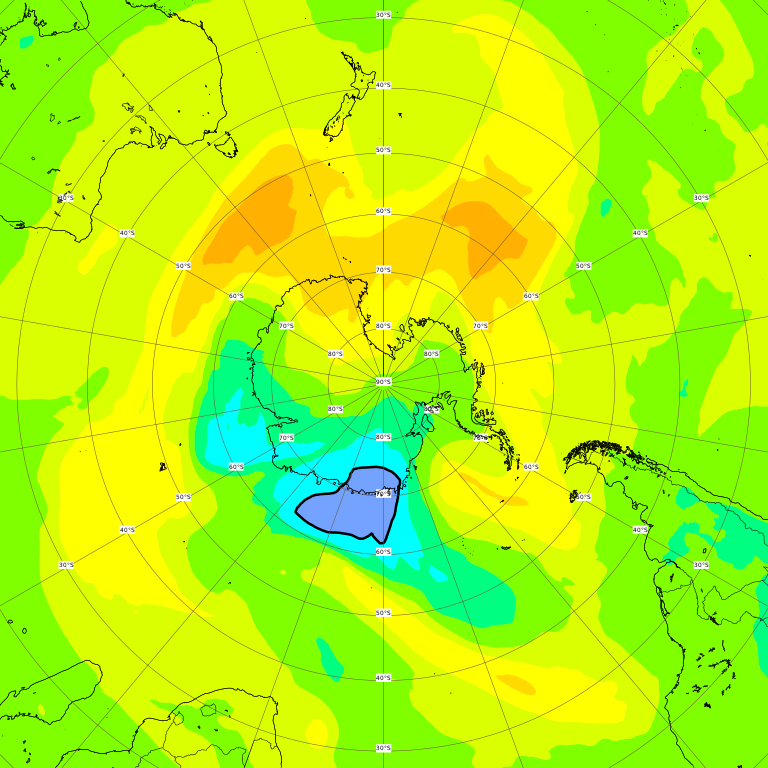

Similar to last year’s season, the service found that the ozone hole in 2021 will be one of the largest and longest-lasting on record, closing later than 95% of all tracked ozone holes since 1979. Computer models of the atmosphere are combined with measurements from satellites and in-situ stations to closely monitor the evolution of the phenomenon. As the stratospheric ozone layer acts as a shield, protecting Earth from potentially harmful ultraviolet radiation, CAMS says it is vitally important to track these changes.

The ozone hole is formed through the accumulation of chlorine- and bromine-containing substances within the polar vortex, where they stay chemically inactive in the darkness. Temperatures in the vortex can fall to below -78°C and ice crystals in polar stratospheric clouds can form; these play an important part in the chemical reactions. As the sun rises over the pole, its energy releases chemically active chlorine and bromine atoms in the vortex, which rapidly destroy ozone molecules, causing the hole to form.

This CAMS program was implemented by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) on behalf of the European Commission, with funding from the European Union. It aims to preserve the ozone layer by continually monitoring and delivering data about its current state.

Vincent-Henri Peuch, director of CAMS at ECMWF, commented, “Both the 2020 and 2021 Antarctic ozone holes have been rather large and exceptionally long-lived. These two longer-than-usual episodes in a row are not a sign that the Montreal Protocol is not working though, as without it, they would have been even larger. It is because of interannual variability due to meteorological and dynamical conditions that can have an important impact on the magnitude of the ozone hole and are superimposed on the long-term recovery. CAMS also keeps an eye on the amount of UV radiation reaching the Earth’s surface, and we’ve seen in recent weeks very high UV indexes – in excess of eight – over parts of Antarctica situated below the ozone hole.”

The Montreal Protocol, signed in 1978, is a climate action agreement to protect the ozone layer. It bans harmful chemicals that are linked to ozone destruction and depletion, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). These chemicals remain in the atmosphere for a long time and reach the stratosphere, where they have been found to contribute to ozone depletion. The Montreal Protocol has ensured that the concentrations of these chemicals are slowly decreasing. However, because of the chemicals’ long lifetimes, this research confirms that it will still take about four decades for the ozone layer to fully recover.

Peuch added, “CAMS monitors and observes the ozone layer by providing reliable and free-to-access data based on different types of satellite observations and numerical modeling, which makes the monitoring of the inception, development and closure of the yearly ozone holes possible in a detailed way. The compiled data, along with our forecasts, allows us to follow the ozone season and compare its development against the ones of the last 40 years.”

Both images ©Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, ECMWF