Rain showers that can develop into downpours with the potential to cause flooding are difficult to predict. However, a novel technique identified by researchers from WUR (Wageningen University & Research), KNMI ( the Dutch national meteorological institute) and weather radar specialists Deltares looks set to improve the accuracy of such forecasts.

The group has been using the signal strength of commercial transmitter masts for cell service to precisely measure the precipitation between two points, but also to develop a forecast for several hours.

Ruben Imhoff of the Wageningen Hydrology and Quantitative Water Management Group collaborated with colleagues from KNMI and Deltares to discover how they might deduce the intensity of rainfall between two masts based on the commercial microwave links (CMLs) between the towers. These CMLs are the radio wave signals used by mobile phone traffic.

“Communication companies are interested in as clear a signal as possible. But we are considering the precise opposite,” explained Imhoff. “The attenuation of the signal may be caused by the intensity of the rainfall between two masts. The more intense the precipitation, the more scrambled our data is bounced back. We map these disruptions and translate them into the intensity of precipitation, as well as into short-term forecasts, also known as nowcasting.”

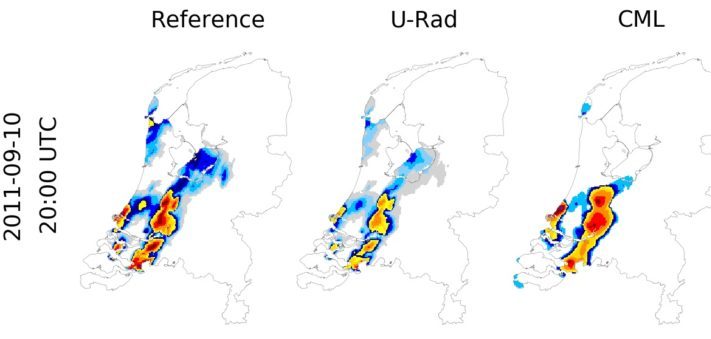

The research team compared data from the KNMI precipitation radars (as used by the Buienradar app and website) with the data obtained from the towers on 12 rainy days. “The results pleasantly surprised us,” remarked Imhoff. “The CML method proves to work fairly well, even during heavy rainfall.” Occasionally, the rain forecast was found to be better than the radar forecast, especially during heavy showers. “However, you must take into consideration that the radar products were not corrected for deviations. Radars too can be improved, and this is currently underway,” he noted.

These findings raise the question of whether CML provides an alternative to radar, which gives a precise overview per square kilometer, including over bodies of water. Imhoff summarized, “Radar provides a stable overview of a large area. Radio wave signals are dense, spaced approximately half a kilometer apart in urban centers, but less so in rural areas. Moreover, the precipitation radar refreshes every five minutes, while the CML data is recorded 15 minutes apart. Increasing the frequency to every five minutes could improve the data. CMLs are a valuable addition to radar data in the Netherlands. These combined images may be used for nowcasting, for example, to predict localized showers.”

The same approach could also be used with new 5G towers, which are even more densely spaced, and, as such, provide more accurate data. However, the researchers don’t yet know how this will work out, as it is unclear how well the CML system works with the higher transmission frequencies employed by 5G. A research proposal for this issue is pending.

The CML system may prove to be particularly useful in countries lacking precipitation radars but with transmitter towers in the urban areas. The KNMI and WUR intend to investigate whether this method may provide short-term forecasts in Nigeria and Sri Lanka.