The glaciers on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State will have largely disappeared by 2070, according to a new study.

The Olympic Mountains, which range from sea level to just under 2,440m in elevation, are almost entirely within the bounds of Olympic National Park on the western peninsula of Washington state. The park hosts approximately 200 glaciers and in recent years typically receives well over 254cm of precipitation, much of which falls as snow.

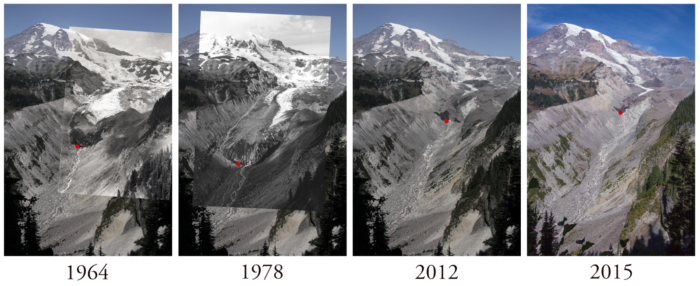

However, since around 1900, the Olympic Peninsula has lost half of its glacier area and, since 1980, 35 glaciers and 16 perennial snowfields have disappeared. Nearly all the glaciers on the peninsula are located within Olympic National Park or are otherwise on surrounding state lands.

Andrew Fountain, lead author and professor of geology and geography at Portland State University, said, “There’s little we can do to prevent the disappearance of these glaciers. We’re on this global warming train right now. Even if we’re super good citizens and stop adding carbon dioxide in the atmosphere immediately, it will still be 100 years or so before the climate responds.”

Even though preventing climate-change-driven glacier disappearances is not likely, ensuring things don’t get worse is a critical goal, Fountain said.

“This is yet another tangible call for us to take climate change seriously and take actions to minimize our climate impact,” he added.

US Geological Survey (USGS) data shows a similar decline of glacier ice in the North Cascades of Washington, farther inland in Glacier National Park, Montana, and farther north in Alaska.

According to USGS research physical scientist Caitlyn Florentine, the new study highlights glaciers’ vulnerability to warmer temperatures in summer, which increases glacial melt, and winter, which decreases glacial growth. “This double whammy has downstream implications for glacier-adapted ecosystems in the US Pacific Northwest,” said Florentine.

Fountain added, “Once you lose your seasonal snow, the only source of water in these alpine areas is glacier melt. And without the glaciers, you’re not going to have that melt contributing to the stream flow, therefore impacting the ecology in alpine areas. That’s a big deal with disastrous fallout.”

The Olympic glaciers are particularly vulnerable to climate change because of their low elevation compared with glaciers elsewhere at higher elevations where temperatures are significantly cooler, such as the Cascade Mountains of Oregon and Washington.

“As the temperatures warm, not only will the glaciers melt more in summer, which you’d expect, but in the wintertime, it changes the phase of the precipitation from snow to rain,” Fountain said. “So the glaciers get less nourished in the winter, more melt in the summer, and then they just fall off the map.”

To view the complete study published today in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research Earth Surface, click here.