Climate scientists at the University of California, Berkeley have found that the apparent temperature, or heat index, calculated by meteorologists and the National Weather Service (NWS) to indicate how hot it feels – taking into account the humidity – underestimates the perceived temperature for the hottest days now being experienced, sometimes by more than 20°F.

The university has asserted that this inaccuracy has implications for those who suffer through these heatwaves because a higher heat index means that the human body is more stressed during these heatwaves than public health officials may realize. This is because sweating and shedding clothes are the main ways humans adapt to hot temperatures and these methods are less effective when the humidity is high.

David Romps, professor of earth and planetary science at UC Berkeley and graduate student Yi-Chuan Lu presented their analysis in a paper accepted by the journal Environmental Research Letters and posted online on August 12.

Romps said, “Most of the time, the heat index that the NWS is giving you is just the right value. It’s only in these extreme cases that they’re getting the wrong number. Where it matters is when you start to map the heat index back onto physiological states and you realize, ‘These people are being stressed to a condition of very elevated skin blood flow where the body is coming close to running out of tricks for compensating for this kind of heat and humidity. So, we’re closer to that edge than we thought we were before’.”

The NWS currently considers a heat index above 103°F to be dangerous, and above 125°F to be extremely dangerous. The heat index was devised in 1979 by textile physicist Robert Steadman, who created simple equations to calculate what he called the relative “sultriness” of warm and humid, as well as hot and arid, conditions during the summer. His model took into account how humans regulate their internal temperature to achieve thermal comfort under different external conditions of temperature and humidity – by consciously changing the thickness of clothing or unconsciously adjusting respiration, perspiration and blood flow from the body’s core to the skin.

In his model, the apparent temperature under ideal conditions – an average-size person in the shade with unlimited water – is how hot someone would feel if the relative humidity were at a comfortable level, which Steadman took to be a vapor pressure of 1,600 pascals. For example, at 70% relative humidity and 68°F – which is often taken as average humidity and temperature – a person would feel like it’s 68°F. However, at the same humidity and 86°F, it would feel like 94°F.

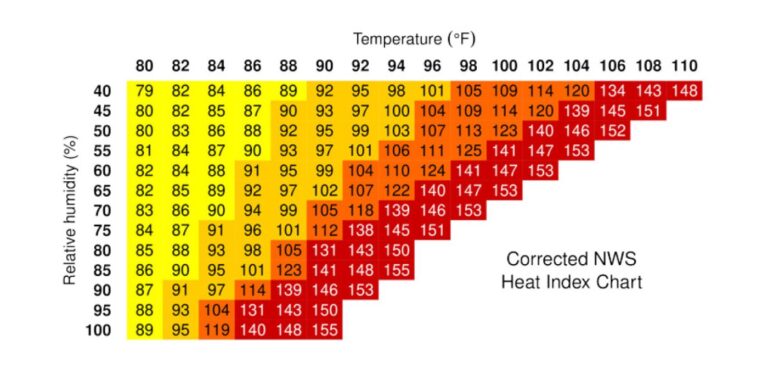

The heat index has since been adopted widely in the USA, including by the NWS, as an indicator of people’s comfort. However, the researchers have highlighted that Steadman left the index undefined for many conditions that are now becoming increasingly common. For example, for a relative humidity of 80%, the heat index is not defined for temperatures above 88°F or below 59°F. Today, temperatures routinely rise above 90°F for weeks at a time in some areas, including the Midwest and Southeast of the USA.

Romps said, “There’s no scientific basis for these numbers. To account for these gaps in Steadman’s chart, meteorologists have extrapolated into these areas to get numbers that are correct most of the time, but not based on any understanding of human physiology. We set out to extend Steadman’s work so that the heat index is accurate at all temperatures and all humidities between zero and 100%.”

One condition under which Steadman’s model breaks down is when people perspire so much that sweat pools on the skin. At that point, his model incorrectly had the relative humidity at the skin surface exceeding 100%, which is physically impossible. That and a few other tweaks to Steadman’s equations yielded an extended heat index that agrees with the old heat index 99.99% of the time, but also accurately represents the apparent temperature for regimes Steadman didn’t calculate because they were far rarer in his time.

When applying the revised heat index equation to the top 100 heatwaves that occurred between 1984 and 2020, the researchers were surprised to find that seven of the 10 most physiologically stressful heatwaves over that time period were in the Midwest not the Southeast, as meteorologists assumed. For example, during the July 1995 heatwave in Chicago in Illinois, which killed at least 465 people, the maximum heat index reported by the NWS was 135°F, when it actually felt like 154°F. The revised heat index at Midway Airport, 141°F, implies that people in the shade would have experienced blood flow to the skin that was 170% above normal. The heat index reported at the time, 124°F, implied only a 90% increase in skin blood flow. At some places during the heatwave, the extended heat index implies that people would have experienced an increase of 820% above normal skin blood flow.

Romps said, “Diverting blood to the skin stresses the system because you’re pulling blood that would otherwise be sent to internal organs and sending it to the skin to try to bring up the skin’s temperature. The approximate calculation used by the NWS, and widely adopted, inadvertently downplays the health risks of severe heatwaves.”

When the skin temperature rises to equal the body’s core temperature (usually 98.6°F), the core temperature begins to increase. The maximum sustainable core temperature is thought to be 107°F – which is the threshold for heat death. For the healthiest of individuals, that threshold is reached at a heat index of 200°F. Fortunately, the research confirms that humidity tends to decrease as temperature increases. So, according to the scientists, Earth is unlikely to reach those conditions in the next few decades. Less extreme, though still deadly, conditions are nevertheless expected to become common around the globe.

Romps said, “A 200°F heat index is an upper bound of what is survivable. But now that we’ve got this model of human thermoregulation that works out at these conditions, what does it actually mean for the future habitability of the US and the planet as a whole? There are some frightening things we are looking at.”