According to new research led by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), emissions associated with mining operations in Africa’s Copperbelt can be quantified from space.

The new study is published in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, and shows for the first time that satellite monitoring can provide valuable information on the impact of the mining boom on air quality in nearby towns and villages. The research also opens the door to the possibility of remotely monitoring increases and decreases in mining activities in a region of the world where surface monitoring is scarce and reporting by mine operators can be inconsistent or altogether absent.

“Mining operations can have a significant impact on quality of life for the people living nearby,” said Pieternel Levelt, director of NCAR’s Atmospheric Chemistry Observations and Modeling Lab and senior author of the paper. “This research can help us better understand how severe and widespread those impacts may be in mining areas like the Copperbelt while also giving us a tool for estimating the growth of mining activities in remote regions that are driving those impacts.”

The work was funded by the US National Science Foundation, which is NCAR’s sponsor, as well as by the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI). The list of co-authors includes researchers from KNMI and the Technical University of Delft in the Netherlands, the Royal Belgium Institute for Space Astronomy, the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado Boulder, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as well as the National Centre for Scientific Research (CRNS) and the Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées, both in France.

An immense increase in production

Africa’s Copperbelt straddles Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, which produced 73% of the world’s supply of cobalt in 2022, according to the Cobalt Institute. Cobalt production in the Copperbelt increased about 600% between 1990 and 2021, according to data from the US Bureau of Mines and the US Geological Survey. This is due to the growing global demand for electric vehicles, laptops, smartphones and other devices that rely on lithium-ion batteries, the vast majority of which contain cobalt.

The vast majority of cobalt is produced as a byproduct of copper mining, though some copper mines do not produce any cobalt. Most of the energy consumed in copper and cobalt mining — including the operation of large machinery and electricity production – is generated by burning diesel fuel, which in turn produces nitrogen oxides, a key ingredient in smog.

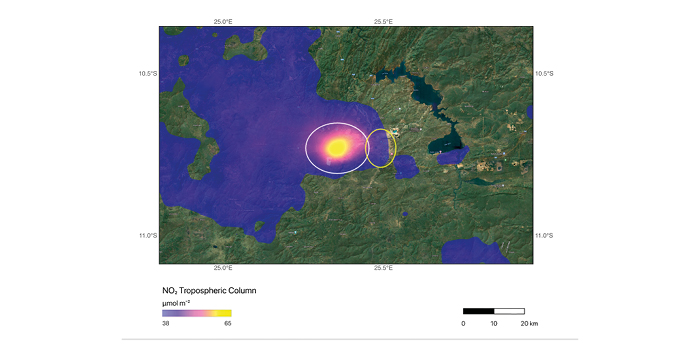

To quantify the emissions, the research team turned to data from the Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) on board the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-5 Precursor satellite (S-5P). TROPOMI can monitor a number of trace gases important for air quality, including nitrogen dioxide.

While biomass burning, urban activity and other industrial operations beyond mining also produce nitrogen dioxide – as do some natural processes – the researchers found that they could distinguish the emissions from copper and cobalt mines in the data. They also found that the annual emissions from each mine strongly correlated with their annual metal production.

“We thought that these copper and cobalt mining operations could affect local air quality; we just didn’t know how much given the lack of ground monitoring in the region,” said NCAR scientist Sara Martínez-Alonso, who is the study’s lead author. “Understanding this is particularly important when mining-related activities proliferate in close proximity to – or even inside of – population centers, as is the case in the Copperbelt. With satellite observations, we were able to quantify emissions from individual mines and put those emissions into perspective.”

The S-5P satellite that carries TROPOMI is polar-orbiting and passes over any given location on the Earth’s surface once a day, limiting the number of observations over the Copperbelt. A geostationary satellite over the continent could provide a much more in-depth picture of emissions in the region, providing hourly instead of daily observations, according to Levelt. Currently, there are no geostationary satellites over Africa or anywhere in the global South.

“A geostationary satellite over Africa could provide the data needed to create accurate air quality forecasts for populations that are at increased risk,” Levelt said. “Hourly observations over urban areas could show the daily evolution of pollution levels and sources, and the information could inform local regulatory agencies.”