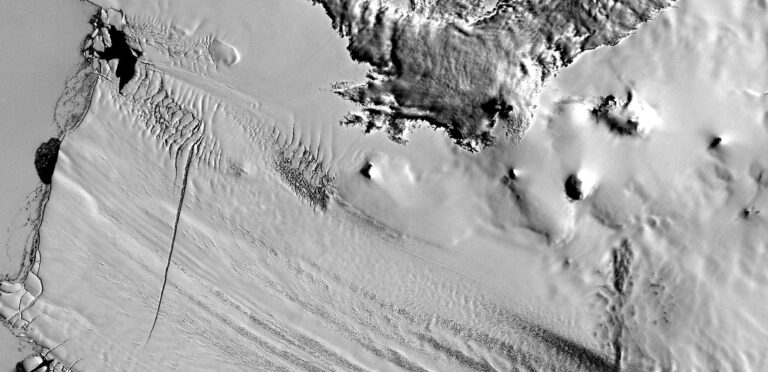

Helped by satellite technology from the European Space Agency (ESA), UK scientists have been tracking the melting of Antarctica’s largest glacier.

Known as Pine Island, the glacier’s disappearing ice represents about 25% of the total Antarctic ice loss. As a consequence the glacier has been studied extensively. But despite this scientists have been unable to agree about the rate at which it is melting.

Some climate models predict a rapid increase in ice loss in the coming decades, while others projections show a more gradual thinning of the glacier, which is 68,000 square miles in size.

A team from the University of Bristol used data from ESA’s CryoSat mission to try and settle the argument about the glacier’s future, which is important since Pine Island has contributed more to sea level rise over the past four decades than any other Antarctic glacier.

The researchers found that the pattern of thinning is evolving in complex ways with thinning rates now highest along the slow-flow margins of the glacier. Meanwhile, thinning rates in the fast-flowing central trunk have decreased by about a factor of five since 2007.

This seems to be a reversal of what was happening prior to 2010.

The results of the new study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, appear to refute the more dramatic ice loss models, suggesting instead that the grounding line, the place where grounded ice first meets the ocean, is unlikely to shift rapidly in the coming decades.

Instead, the results support model simulations that show the glacier losing mass at rates not much higher than at present.

The study’s lead author Professor Jonathan Bamber, of the University of Bristol’s School of Geographical Sciences, said, “This could seem like a ‘good news story’ but it’s important to remember that we still expect this glacier to continue to lose mass in the future and for that trend to increase over time, just not quite as fast as some model simulations suggested.”