The hole in the ozone layer above the Antarctic is continuing to decrease, according to NOAA and NASA scientists.

The hole in the ozone, the portion of the stratosphere that protects the planet from the sun’s ultraviolet rays, has an average area of 23.2 million square kilometers. That measurement is slightly smaller than the 23.3 million square kilometers reached last year, and well below the average seen in 2006 when the hole size peaked.

Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said, “Over time, steady progress is being made and the hole is getting smaller. We see some wavering as weather changes and other factors make the numbers wiggle slightly from day to day and week to week. But overall, we see it decreasing through the last two decades. Eliminating ozone-depleting substances through the Montreal Protocol is shrinking the hole.”

The ozone hole appears when the protective ozone layer in the stratosphere above the South Pole begins to thin every September. Chlorine and bromine derived from human-produced compounds are released from reactions in high-altitude polar clouds. The chemical reactions then begin to deplete the ozone layer as the sun rises at the end of the winter in the southern hemisphere, with the strongest depletion occurring above Antarctica.

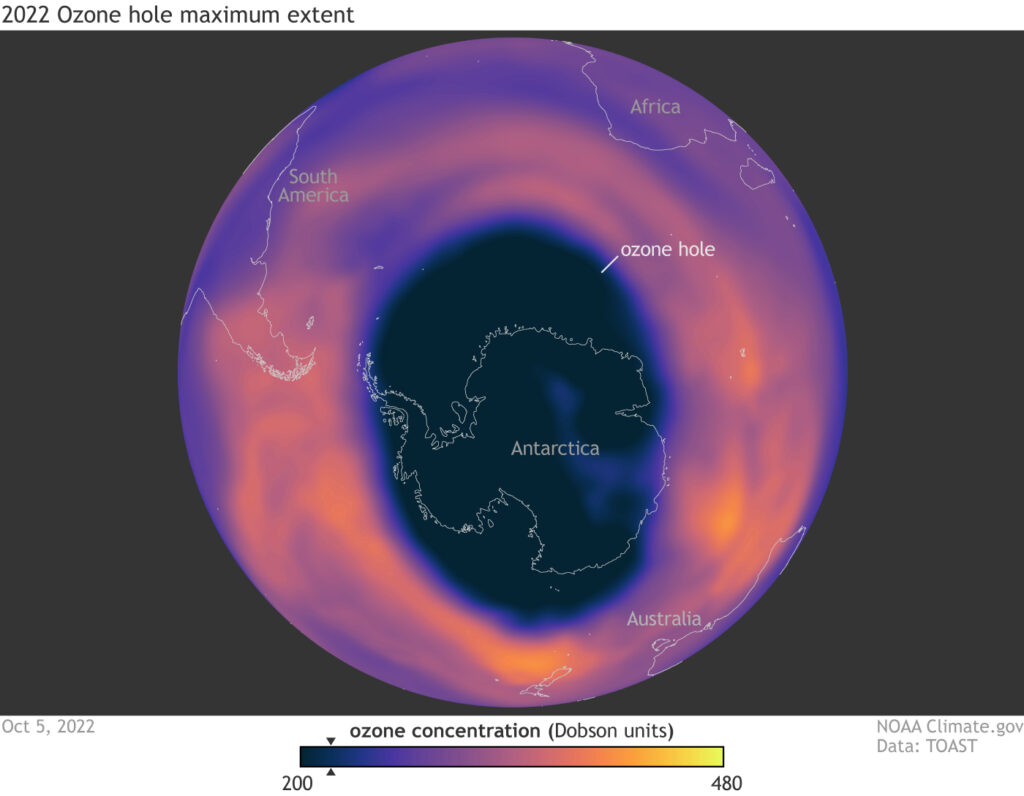

NOAA and NASA researchers detect and measure the growth and breakup of the ozone hole with satellite instruments aboard Aura, Suomi-NPP and NOAA-20 satellites. This year, satellite observations determined that the ozone hole area reached a single-day maximum of 26.4 million square kilometers on October 5, but is now shrinking.

NOAA scientists at the South Pole Station also record the ozone layer’s thickness by releasing weather balloons carrying ozonesondes that measure the varying ozone concentrations, measured in Dobson units, as the balloon rises into the stratosphere.

The lowest column amount detected by ozonesondes at the South Pole this year was 101 Dobson units on October 3, according to Bryan Johnson from NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory. This is very similar to last year’s measurements. At altitudes between 14 and 21km, the ozone was almost completely depleted when the ozone hole was at its maximum.

Measurements made via satellite and ozonesondes show that the Antarctic ozone hole has been smaller in recent years than it was in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This is due to the Montreal Protocol, a treaty adopted 35 years ago to ban the release of harmful ozone-depleting chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). It remains the only international treaty ratified by every country on Earth. Amendments have helped it evolve to meet new scientific, technical and economic developments and challenges.

Scientists were also concerned about the potential stratospheric effects of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano eruption on January 15, 2022, but so far, no direct effects on the ozone layer have been noted in the data.