NOAA has released the 2023 Arctic Report Card, which documents new records showing that human-caused warming of the air, ocean and land is affecting people, ecosystems and communities across the Arctic region, which is heating up more quickly than any other part of the world.

The report reveals that summer surface air temperatures during 2023 were the warmest ever observed in the Arctic, while the highest point on Greenland’s ice sheet experienced melting for only the fifth time in the 34-year record. Overall, it was the Arctic’s sixth-warmest year on record. Sea ice extent continued to decline, with the last 17 Septembers now registering as the lowest on record. These records followed two years when an unprecedented high abundance of sockeye salmon in western Alaska’s Bristol Bay contrasted with record-low Chinook and chum salmon, which led to fishery closures on the Yukon River and other Bering Sea tributaries.

“The overriding message from this year’s report card is that the time for action is now,” said NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad. “NOAA and our federal partners have ramped up our support and collaboration with state, tribal and local communities to help build climate resilience. At the same time, we as a nation and global community must dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions that are driving these changes.”

The annual Arctic Report Card, now in its 18th year, is the work of 82 authors from 13 countries. It includes a section titled Vital Signs, which updates eight measures of physical and biological changes, four chapters on emerging issues and a special report on the 2023 summer of extreme wildfires.

Indigenous knowledge

The 2023 report card features two chapters on the importance of implementing Indigenous knowledge for the future resilience of the Arctic. One chapter describes the work of the Alaska Arctic Observatory and Knowledge Hub, a collaboration between the University of Alaska scientists and a network of Iñupiaq observers who are documenting long-term environmental change and social and cultural impacts on their northern Alaska communities.

The value of Indigenous and local knowledge to help tackle environmental challenges is also central to a chapter on the restoration of peatlands and boreal forests in Finland, where Indigenous Sámi people and Finnish villages are working with scientists to restore these wetland ecosystems and forests.

Over the last two decades, the Finnish nonprofit Snowchange Cooperative has restored dozens of sites, positively influencing 52,000ha of peatlands and forest damaged by decades of industrial harvesting and forest management. The restoration demonstrates a climate solution that increases carbon storage, preventing greenhouse gas emissions from entering the atmosphere. The restored peatlands are also reportedly restoring water quality and bringing back fish and birds, a vital food source and attraction for ecotourism.

Another new chapter delves into the little-known topic of subsea permafrost, a potential source of greenhouse gas emissions. For thousands of years as the world emerged from the last ice age, rising ocean waters in the Arctic continued to cover more and more permafrost, transforming it into subsea permafrost. The Arctic has an estimated 2,500,000 square kilometers of subsea permafrost, a fifth of the amount of permafrost found on land. According to NOAA’s report, international research collaboration is needed to address questions about the extent and current state of subsea permafrost and estimate the potential release of greenhouse gases as it thaws.

Annual updates of vital signs for 2023

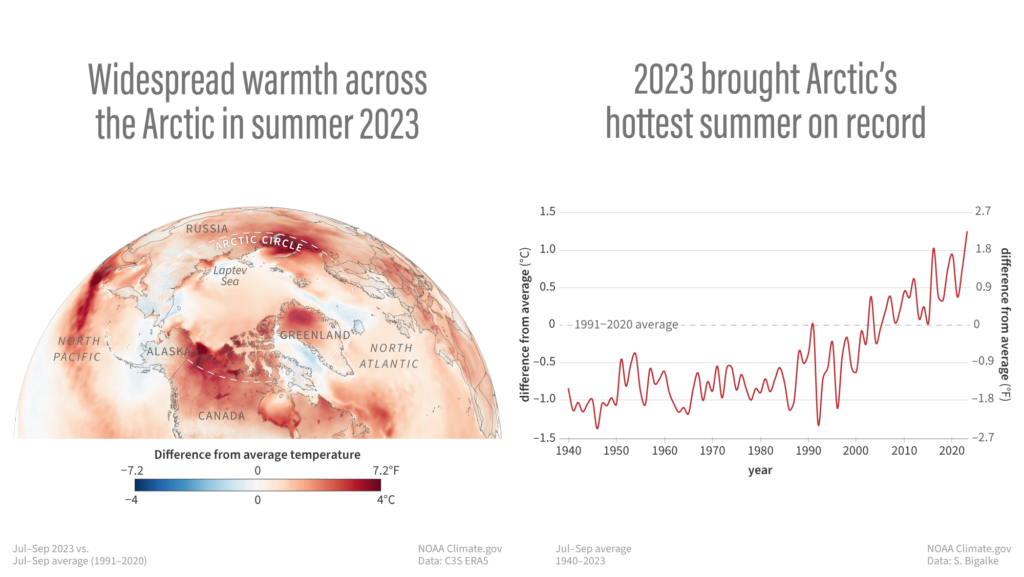

The researchers found that the average surface air temperature in the Arctic this past year was the sixth warmest since 1900 at -7°C. The summer Arctic average temperature was reportedly the warmest on record at 6.4°C. Data shows that since 1940, annual average temperatures have risen 0.25°C per decade and average summer temperatures have risen 0.17°C per decade.

According to the report, sea ice extent continues to decline, with the 17 lowest Arctic sea ice extents on record occurring during the last 17 years. 2023’s sea ice extent was found to be the sixth lowest in the satellite record, which began in 1979, with older, thicker multi-year ice far less abundant than in the 1980s.

Mean sea surface temperatures in August 2023 were also reportedly 5-7°C warmer than the 1991-2020 August mean values in the Barents, Kara, Laptev and Beaufort seas. Unusually cool August temperatures were observed in Baffin Bay, Greenland Sea and parts of the Chukchi Sea. August mean sea surface temperatures show warming trends for the period from 1982 to 2023 in areas of the Arctic Ocean that are ice-free in August, with mean sea surface temperature increases of nearly 0.5°C per decade.

Arctic Ocean regions, except for the Canadian Archipelago, Chukchi and Beaufort seas, continued to show increased ocean phytoplankton blooms, or primary productivity, with the largest increases in the Eurasian Arctic and Barents Sea.

North American snow cover set a record low in May 2023, while snow accumulation during the 2022-2023 winter was above average across both North America and Eurasia. Heavy precipitation events broke existing records at various locations across the Arctic, with some variation – such as a dry summer in northern Canada – contributing to record wildfires. Pan-Arctic precipitation was the sixth highest on record, continuing the trend toward a wetter Arctic.

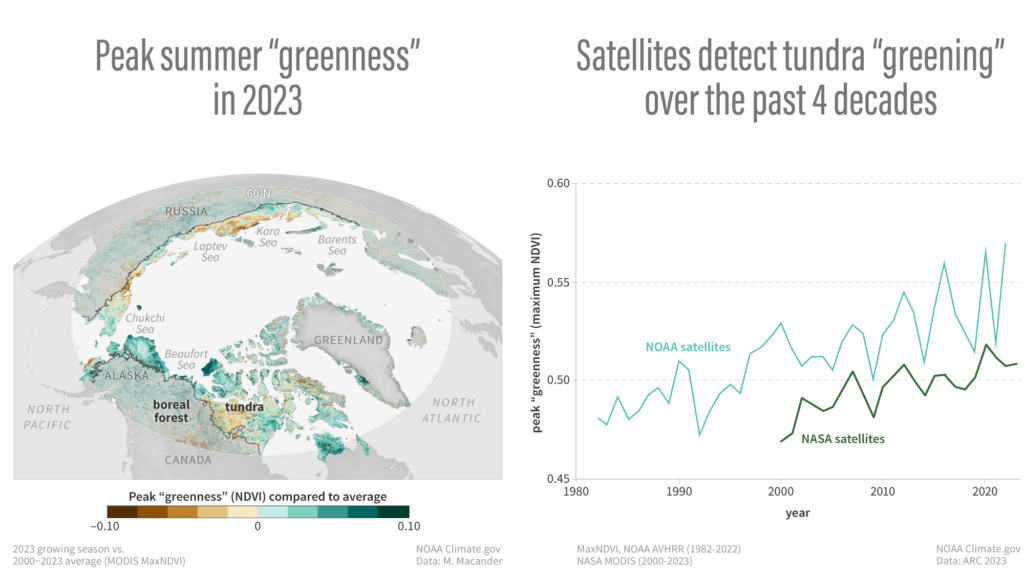

The scientists also found that tundra greenness across the Arctic was the third highest in the 24-year satellite record, a slight increase over 2022. The Arctic was seen to continue a trend of increased shrubs, willows and alders where once there was tundra.

Alongside this, the Greenland Ice Sheet reportedly continued to lose mass despite above-average winter snow accumulation. Summit Station, the highest point on the ice sheet, reached a temperature of 0.38°C on June 26, 2023, experiencing melting for only the fifth time in the 34-year record.

To watch NOAA’s corresponding 2023 Arctic Report Card video, click here.