Marine scientists have deployed two hi-tech bottom pressure recorders (BPRs) on either side of the Atlantic Ocean to measure the strength of global ocean currents that drive much of the Earth’s climate.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a large system of ocean currents that transports warm surface waters from the tropics northward toward the subpolar and Arctic regions. There, the waters cool, become denser and sink before returning southward at depth. In doing so, this vast ‘conveyor belt’ movement of water is a major factor in controlling global heat distribution, regional sea level changes, the ocean’s absorption of carbon and European weather.

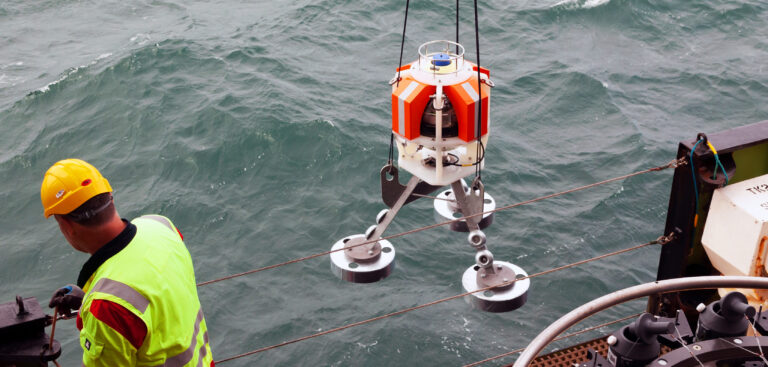

To measure the AMOC’s impact on the changing climate, scientists from the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) in Oban, Argyll, have deployed two deep-sea BPRs, one in the northeast Atlantic and one in the Labrador Sea, to record regular changes in sea surface height.

The two Fetch Ambient-Zero-Ambient (AZA) BPRs, developed and built by UK marine technology firm Sonardyne, have been placed thousands of meters below the sea surface where they will record sea surface height to the nearest centimeter, giving the researchers a detailed comparison between the two locations. Deployed for up to 10 years, this will enable them to measure changes in the speed and strength of the AMOC, which will provide crucial data to inform climate predictions.

The northeast Atlantic instrument was deployed from the RRS James Cook during the Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Programme (OSNAP) research cruise, jointly led by SAMS and the UK’s National Oceanography Centre (NOC) in August 2022. The western instrument was deployed by SAMS oceanographer Dr Sam Jones during a cruise on board the RV Meteor, led by the German marine institute GEOMAR in September 2022.

Dr Kristin Burmeister, SAMS oceanographer and co-chief scientist on the OSNAP cruise, said, “This is the first time these Sonardyne pressure sensors have been used in ocean physics, but they could be a game changer in how effectively we can measure the vast AMOC. Once we know the speed of these currents, we can work out the volume of water being moved and then calculate how much heat is being transported. This heat is important to the climate of Europe and gives the continent its relatively mild weather. These currents directly impact our weather, particularly in the UK. The influence of the AMOC on the Earth’s climate is so significant that there is an urgent need to better understand its movement, speed and heat transfer. That data will allow us to feed into the various climate models that help governments and society prepare for the changes in our climate in years to come.”

The east side of the Atlantic Ocean is typically around 20cm higher than the west side but the flow of the water does not go east to west, as the opposing force of the Coriolis effect from the rotating Earth causes a circular flow in a general south to north movement.

The AMOC transports roughly 1.25 Peta (10^15) watts of energy from the Tropics toward the subpolar and Arctic regions – more than 60 times the present rate of world energy consumption. Despite being so influential in our climate, it has only been continuously measured for 19 years, limiting our long-term understanding of its relation to climate.

The BPRs will remain on the seabed for up to 10 years and the data they gather can be transmitted wirelessly through the water to a ship or even an uncrewed platform, without the need to recover them.

Geraint West, head of science at Sonardyne, said, “AZA is a game-changing technology as, previously, the need to calibrate pressure sensors meant that lengthy observations were compromised, limiting their use for long-term studies. The AZA technique used in the Fetch AZA overcomes this by autonomously recalibrating in situ with an internal high accuracy barometer. This allows consistently accurate readings for up to 10 years. Mastering this technique took years of investment by Sonardyne and while it’s already been used, at scale, in other sectors, we are hugely excited to see it now being put into use in physical oceanography, not least in a project that will aid our understanding of key climate drivers.”