The UK Met Office has published a data set which shows the importance of humidity on global heat extremes.

The HadISDH.extremes data set developed by Met Office scientists monitors both temperature and humidity across the globe over long periods of time. It provides insight into how combined heat and humidity events around the world are changing over time. The methodology behind the HadISDH.extremes data set has been published in the journal Advances in Atmospheric Sciences accompanied by an analysis of humid heat extremes using the new data.

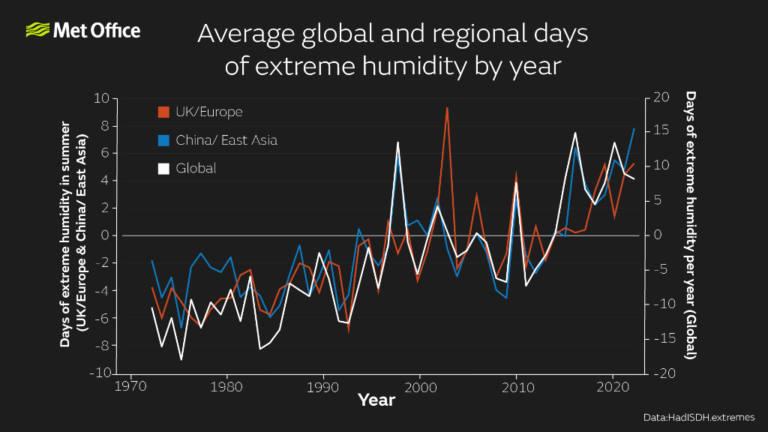

Analysis of the new data has shown that the global annual/seasonal mean of maximum daily wet bulb temperature, a measure of humidity, has increased by around 0.2°C each decade between 1973-2022. This rate of change is even higher when looking at the summer months in the UK and Europe, with an increase of around 0.3°C each decade over the same period. Although a seemingly small figure over decades, the increase in severe humidity events can have an impact on human health and productivity.

Humidity can be defined in several different ways, but a common measure is the wet bulb temperature. This is a measure of how saturated the air is, determined by using a thermometer covered in material saturated with water. Evaporation of the water has a cooling effect on the thermometer and can readily occur up to the point where the air becomes saturated – at which point the wet bulb temperature is then equal to the dry bulb temperature.

Although human skin temperature can vary quite a lot, on average it is between 33°C and 37°C. Generally, the wet bulb temperature is below this level, so water (sweat) can be readily evaporated away from the skin, leaving the skin cooler as a result, just like the wet bulb thermometer. However, if the wet bulb temperature reaches a similar level to skin temperature, the body’s ability to cool itself through evaporation is significantly reduced. It is for this reason that atmospheric conditions where the wet bulb temperature is 35°C or above are considered uninhabitable for humans.

The data has also uncovered new ways of examining different types of heat events, for example ‘hot and dry’, ‘hot and humid’ or ‘warm and humid’. Each of these types of extreme heat has different characteristics and requires different cooling methods to combat the effects of the type of heat. The new data set enables users to assess what sort of heat events are being experienced in different regions or seasons. This is intended to help with adaptation measures to cope with a changing climate.

For instance, there may be occasions where an extreme heat event might not be detectable from daytime maximum temperatures, yet significant impacts may result from high humidity. These events might not be flagged as dangerous but can still have impacts on how people feel and could lead to lower levels of productivity. The research calls these events ‘stealth heat events’.

Dr Kate Willett, expert climate monitoring scientist at the Met Office, said, “We know that our atmosphere is warming and that temperature extremes are increasing in frequency and magnitude, and there are well-established data sets that have tracked these changes over a long period of time. That hasn’t previously been true for humid heat extreme:, this new data set aims to fill that gap by providing a global, long-term data set for humid heat extremes.

“Humidity is a critical meteorological factor to track, as it has a profound impact on human and animal health and productivity. A wet bulb temperature of 35°C is a threshold where the human body can no longer cool itself through evaporation of sweat. What we can see from this new data set is that humidity is increasing across the globe but at faster rates in particular regions and during different seasons. Continued increases in humidity as our climate warms will see increasing extreme events where heat stress becomes a hazard, and even areas of the world which are no longer habitable for humans.”

For more key data updates from the meteorological technology industry, click here.