Weather and environmental measurement specialist Vaisala is celebrating 40 years of operating its US National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN).

Over the years, the lightning data provided by the NLDN has enabled meteorologists to improve thunderstorm forecasts; energy and infrastructure companies to better protect critical power, utility and communications systems; and airports to safely operate flights.

Ryan Said, senior scientist at Vaisala Xweather, said, “Everyone in the US benefits from the NLDN, either directly or indirectly. Globally, 80% of all national meteorological agencies, including the National Weather Service, that need lightning data, have chosen to use ours to help people stay safe from one of nature’s most violent forces.”

During the time that the US NLDN has been operating, lightning-related deaths or injuries have dropped from an average of 69 deaths per year from 1983 to 1998, to 24 from 2007 through to 2022.

The NLDN detected its first cloud-to-ground lightning strike on June 1, 1983, about three miles northwest of New Milford, Pennsylvania. In 1989, the NLDN became the first lightning detection network to reach complete coverage of the continental USA. The network has been under constant development and can now measure lightning down to an accuracy of 100m anywhere in the continental USA.

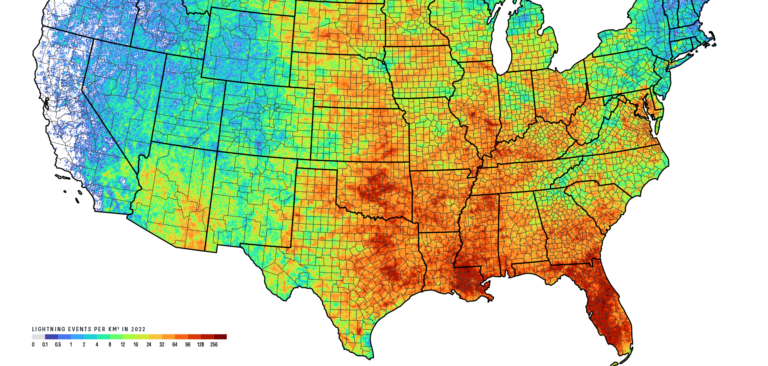

In 2022, the NLDN detected nearly 200 million lightning events in the USA. The latest advancement added to the NLDN in 2022 is Strike Damage Potential, which identifies unique strike points on the ground and helps to assess the potential damage caused by a lightning flash.

Said added, “Lightning strikes aren’t all the same – some lightning is more likely to cause significant damage to buildings, towers and wind turbines. Lightning can even start wildfires. We can provide people with near real-time insight on whether a lightning strike merits further investigation mere minutes after the flash and boom.

“Climate change makes lightning activity more unpredictable. We have already detected an increase in lightning close to the North Pole since we started keeping records of Arctic lightning in 2012. Because of the weather conditions that far north, lightning should be quite rare near the Pole. In the US, we also saw an unusual lack of thunderstorms that likely led to the Mississippi River drying out last year.”