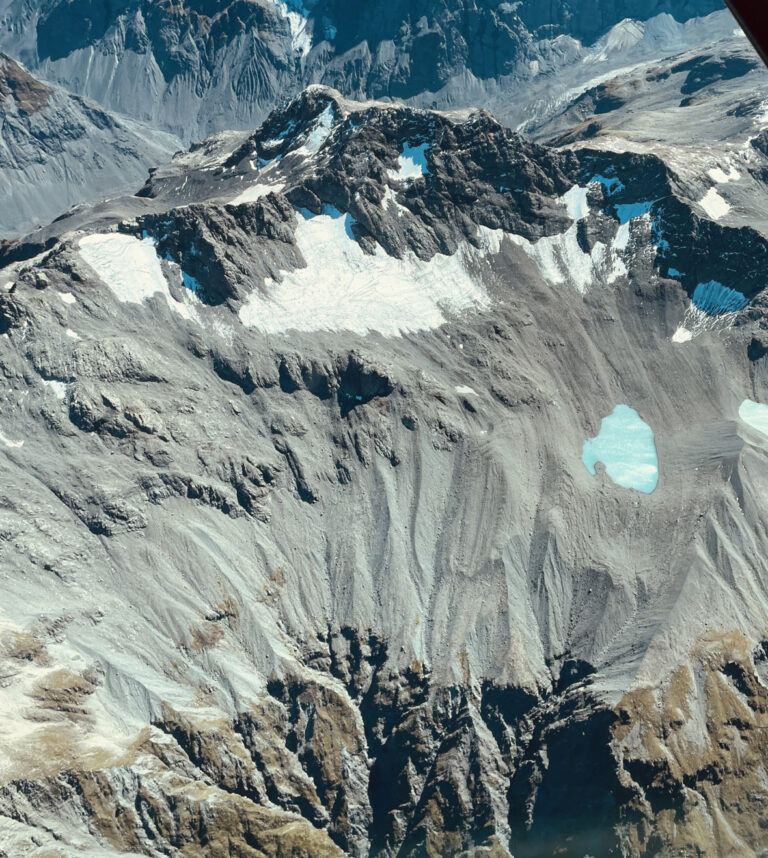

According to NIWA’s latest end-of-summer snowline survey, New Zealand’s glaciers appear “smashed and shattered” due to enduring ice loss.

Dr Andrew Lorrey’s research

Dr Andrew Lorrey is the program lead and NIWA’s principal scientist of climate and environmental applications. He said the research paints a picture of how Aotearoa’s landscape is transforming.

“This year, we covered nearly the full set of index glaciers that have been monitored since the 1970s. We flew to the southernmost glaciers, ones that we’ve not seen since 2018. Back then, they were incredibly small and functionally dead, and one is now two-thirds of the size it was on our last visit. Overall, the snowline has been rising and in the most recent years we’re seeing that rise accelerate, so we’re experiencing a continued trend of glacial ice loss,” said Dr Lorrey.

The past decade has seen seven of the 10 warmest years that New Zealand has experienced since records began. Last year was the second warmest year on record – a trend that followed the rest of the world, with 86% of the planet having above-average temperatures that year.

“Even if we got a few cooler seasons, they wouldn’t be enough to undo the damage that’s already been done. My colleague Dr Trevor Chinn, who started the survey nearly 50 years ago, put it perfectly – he said that the difference between today and five decades ago is like going to a ski field in the summer and then in the winter. That’s how stark it is, and it’s not just happening in New Zealand but all over the world,” said Dr Lorrey.

New Zealand’s mountain ranges

Since the 1970s, NIWA has been flying over Aotearoa New Zealand’s mountain ranges to conduct its end-of-summer snowline survey, observing the state of glaciers and elevation of the snowline.

Glaciers feed New Zealand’s meltwater, which sustains stream habitats, as well as delivering nutrients into lakes, rivers and oceans. They also feed hydroelectric lakes, affecting the availability of renewable energy, and contribute millions of dollars to New Zealand’s economy through tourism (estimated at NZ$100m [US$60m] in 2007).

“New Zealand is one of the few mid-latitude places where people live near glaciers, where people can see and visit them easily. But this is getting tougher. Tourism operators are having to penetrate further and further into the mountains to reach them.

“They hold tremendous value, but I worry that they won’t be around for our children to enjoy. Not to mention the impacts their disappearance will have on our environment and cultural heritage. A warming planet means fewer cold places and less ice. The message remains the same: we must tackle the issue of rising greenhouse gases if we are to save our glaciers from melting away,” said Dr Lorrey.

In related news, a study from New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) has mapped the immediate aftereffects of the January 2022 eruption of Hunga Tonga – Hunga Ha’apai, highlighting the risks of similar events. Click here to read the full story.