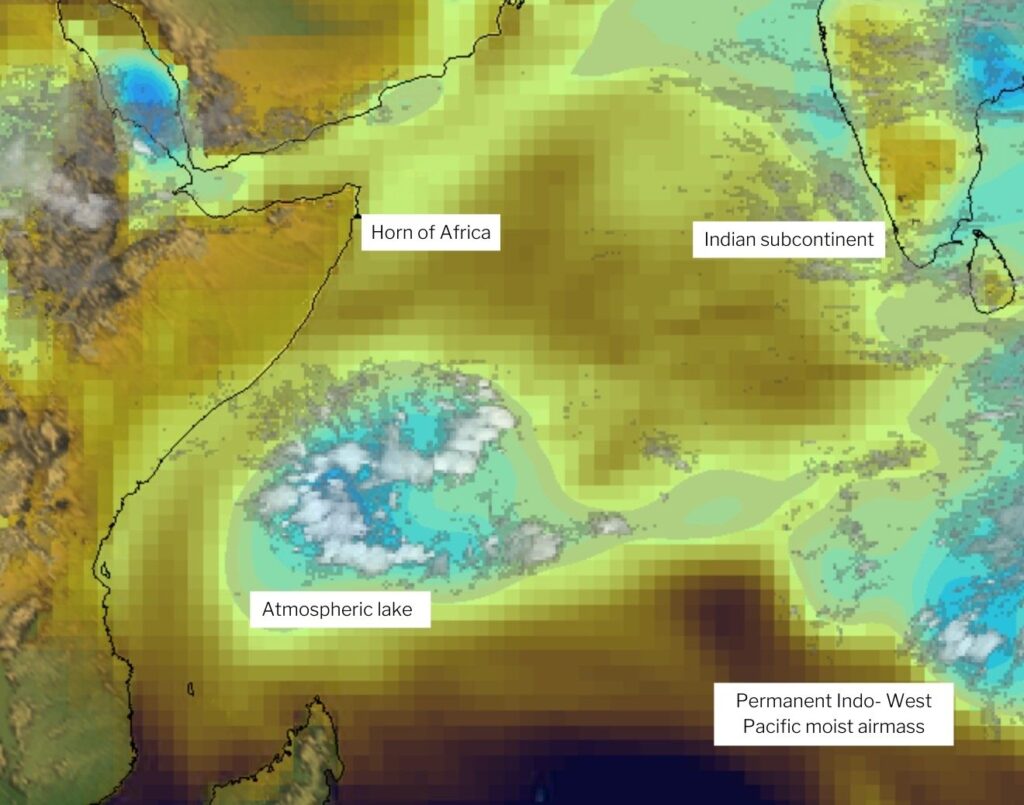

Research from the University of Miami has identified a new meteorological phenomenon called an ‘atmospheric lake’, a compact pool of moisture originating over the western Indian Ocean which brings water to dry lowlands along East Africa’s coastline.

Like the better-known atmospheric rivers, atmospheric lakes start as filaments of water vapor in the Indo-Pacific but are defined by the presence of water vapor concentrated enough to produce rain, rather than being formed and defined by a vortex, like most storms. Unlike the fast-flowing atmospheric rivers, the smaller atmospheric lakes detach from their source as they move at a sedate pace toward the coast.

Atmospheric lakes begin as water vapor streams that flow from the western side of the South Asian monsoon and pinch off to become their own measurable, isolated objects. They then float along ocean and coastal regions at the equatorial line in areas where the average wind speed is around zero.

In an initial survey to catalog such storms, Brian Mapes, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Miami, used five years of satellite data to spot 17 atmospheric lakes lasting longer than six days and within 10 degrees of the equator, in all seasons. Lakes farther off the equator also occur and sometimes become tropical cyclones.

The atmospheric lakes last for days at a time and occur several times a year. If all the water vapor from these lakes were liquified, it would form a puddle only a few centimeters deep and around 1,000km (620 miles) wide. This amount of water can create significant precipitation for the dry lowlands of eastern African countries where millions of people live, according to Mapes.

“It’s a place that’s dry on average, so when these [atmospheric lakes] happen, they’re surely very consequential,” Mapes said. “I look forward to learning more local knowledge about them, in this area with a venerable and fascinating nautical history where observant sailors coined the word monsoon for wind patterns, and surely noticed these occasional rainstorms, too.”

Weather patterns in this region of the world have received little attention from meteorologists, limited mostly to studies of rain and water vapor on a monthly rather than day-to-day scale, according to Mapes. He is working to understand why atmospheric lakes pinch off from the river-like pattern from which they form, and how and why they move westward. This might be due to some feature of the larger wind pattern, or perhaps that the atmospheric lakes are self-propelled by winds generated during rain production.

These are questions that would need to be answered before Mapes and other researchers can begin to study how climate change could affect atmospheric lake systems. He plans to study these events more closely using satellite data and will look into the possibility that these atmospheric lakes occur elsewhere in the world.

“The winds that carry these things to ashore are so tantalizingly, delicately near zero [wind speed], that everything could affect them,” Mapes said. “That’s when you need to know, do they self-propel, or are they driven by some very much larger-scale wind patterns that may change with climate change.”